A pair of lost statues may be the key to learning more about Ancient Greek leg locks in Pankrátion.

One of the tragedies that few talk about following the bombing of Europe in the Second World War is the destruction of countless antiquities from the ancient past that were housed in museums and private collections. Much was lost and some are known to us only through documentation.

Two of these lost pieces, both of which were housed in private collections and were unseen for an extremely long time even before the War, depict Ancient Greek leg locks from Pankrátion. As there is scant surviving evidence of the leg lock game of pankratiasts, the drawings of these two sculptures are invaluable.

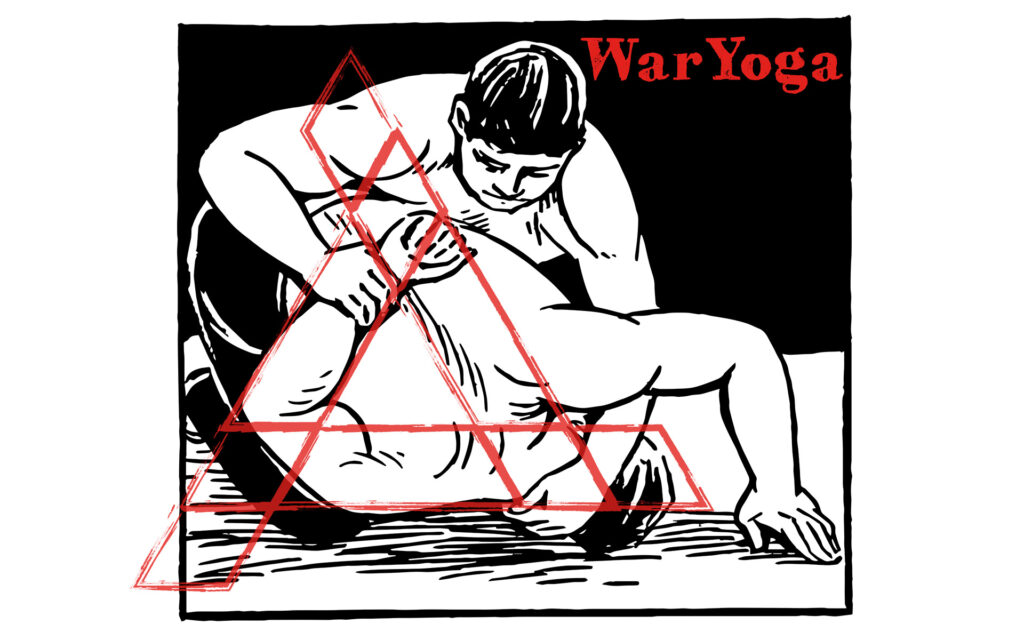

The first is recorded by French Benedictine monk Bernard de Montfaucon in his 1719 work L’antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures (Antiquity Explained and Represented in Sculptures). The alabaster statue depicts a fighter on the ground and another above. In his 1722 translation of Montfaucon, David Humphreys puts it thus:

“The engagement was not over upon the fall of one of the Parties, as appears by the two Wrestlers of Alabaster in our cabinet; one of which has given the other a Fall, who tho’ he is down, yet still appears to contend, and gives the other a kick upon the Face with his Foot.”

The passage was written by a monk and translated by a university academic, both of whom had little knowledge of combat sports (although Montfaucon was a soldier before he was a monk). At this time, little was known of Pankrátion and neither appears to know of its existence, as the scene is described as wrestling.

A modern observer will note two things – first the mentioned “up kick” familiar to us through MMA, but also that both of the fighters appear to be fighting for leg locks. We know from other evidence that standing leg locks were performed, but here is a critical piece of the puzzle, showing the grounded fighter collecting the knee.

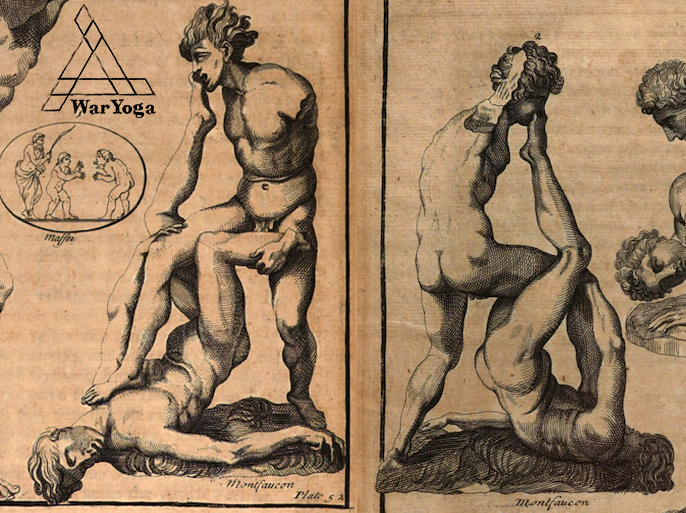

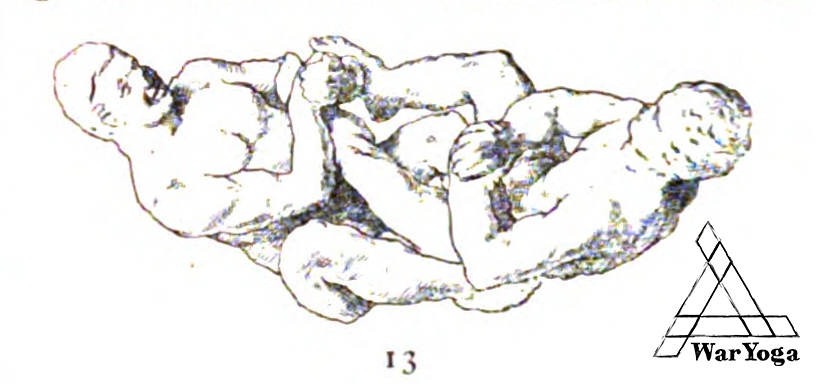

The second sculpture is recorded in the 1890 edition of Archäologischer Anzeiger, published in Vienna. One of the articles in the annual journal depicts several works held in private collections in Leipzig. A bronze from the collection of Theodor Graf is of extreme interest. The journal has this to say:

“Group of foot fighters. Full casting. Apparently of good workmanship, but very destroyed. Both athletes have their legs crossed in the same position, their hands folded. Perhaps a form of combat in which the hands were not allowed to participate and therefore had to remain clasped together. Could have been jewellery or the handle of an implement, but there is no recognisable point of attachment.” (Translation Tom Billinge 2025)

This small bronze is again described by an academic who has never seen leg locks, as submission wrestling was rare in central Europe. German ganzer ringkampf, which allowed ground fighting was relatively obscure by the late 19th century, Catch Wrestling had not really taken off in Europe and the Japanese arts had not yet reached the continent. A modern practitioner can easily identify two fighters hunting for a leg lock, both with a gable grip, rather than the more often seen “meandros grip.”

We are fortunate that these two images were recorded, as they provide critical evidence of Ancient Greek leg locks. As the artists were unfamiliar with the techniques, the rendering of the originals to illustration likely is an accurate portrayal as they did not have any other frame of reference to to colour their imagination. These two lost artifacts show us that no matter how sophisticated we believe our modern combat sports to be, there is nothing new under the sun.