Dotted across the Peloponnese and the island of Thera are four lifting stones of ancient Greece.

Today, there is no trace of Stonelifting in Greece, but four relics of the athletic past of the Hellenic people tell a story of a strength culture of deep antiquity that once thrived in Hellas.

The four recorded lifting stones of ancient Greece are the oldest known stones with that purpose in the world. While Stonelifting is almost universal and clearly extremely ancient, there are no other stones that we know to have been lifted that are older than the Greek stones.

Luckily for us, the Greeks have always had the inclination to boast of their deeds. It is a cultural heritage that can be found in the heroes of the Iliad vaunting over their defeated adversaries as well as in a cafenion in 21st century Athens. Each of the extant stones is inscribed with the name of who lifted it and how he did so.

Bybon Stone

While the other three lifting stones of ancient Greece are less well-known, many with an interest in strength culture knows of the Bybon Stone.

The stone was unearthed in the southern part of the Pelopion (shrine of Pelops) in the sacred Altis area of the Olympic sanctuary on the 5th of June 1879. This means that the stone was dedicated at the sanctuary

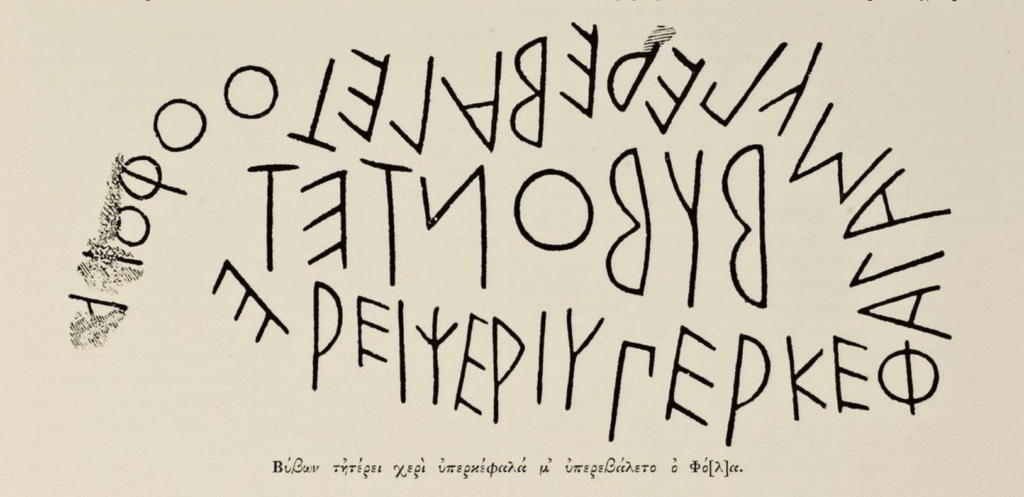

Now found in the Museum of the History of the Olympic Games in Olympia, Greece, the 143.5 kg (316 lb) sandstone block dates from between the late 7th to early 6th century BCE, making it the oldest known lifting stone on the world. It bears the wonderful inscription:

“Bybon, son of Phola, has lifted me over his head with one hand.”

This phrasing has been the cause of much debate over the years with the two grooves like a handle cut into the top of the stone coming into the debate. Was the claim just an exaggerated boast, or did Bybon lift it with one hand, and if so, how? Another complication comes since it can also be translated as “threw me over his head.” This opens the possibility of putting the stone in the manner of the ancient Scots.

It is a mystery that will remain as such, as the museum isn’t going to let anyone try and copy Bybon anytime soon.

Eumastas Stone

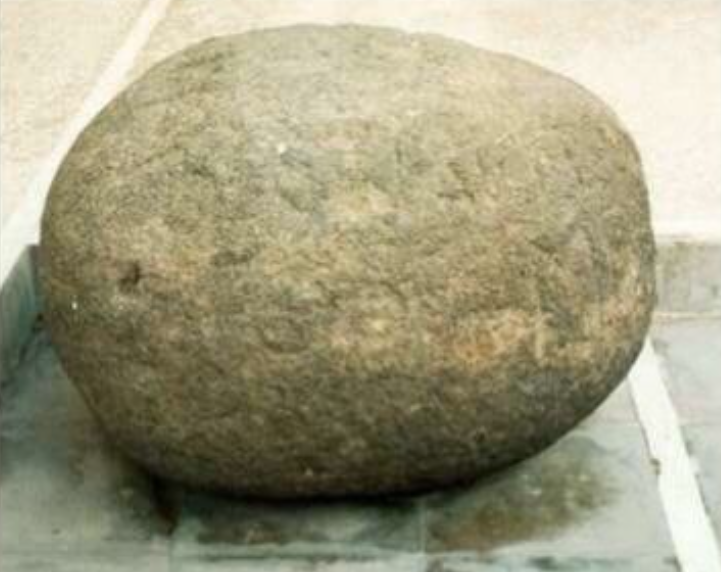

The other somewhat known lifting stone of Ancient Greece is the 480 kg (966 lb) Eumastas stone on the island of Thera (Santorini) found in a vineyard wall on the southern foot of Mount Prophet Elias in the late 19th century.

A large round volcanic trachyte boulder, it is contemporary with the Bybon Stone, dating from around the 6th century BCE. It can be found in the Archaeological Museum of Thera. The stone is spirally inscribed with what could only be described as a hav lift:

“Eumastas, son of Kritobolos, lifted me off the earth.”

This weight is enormous and the stone has no discernible handles, making it an extremely difficult stone to get of the ground for any strength athlete alive today.

While both the Bybon and Eumastas Stones are acknowledged by their relative museums as being lifting stones, the story of the other two stones has required some detective work. I first read about them in H. A. Harris’ 1972 work Sport in Greece and Rome. Harris records the four ancient stones, but is somewhat incredulous, putting forward the theory that they are all hoaxes. Regardless, Harris recorded the inscriptions and the location of them in the old Inscriptiones Graecae volumes published in Germany in Latin in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. From these volumes of inscriptions, I was able to find the last recorded location of both of the other stones.

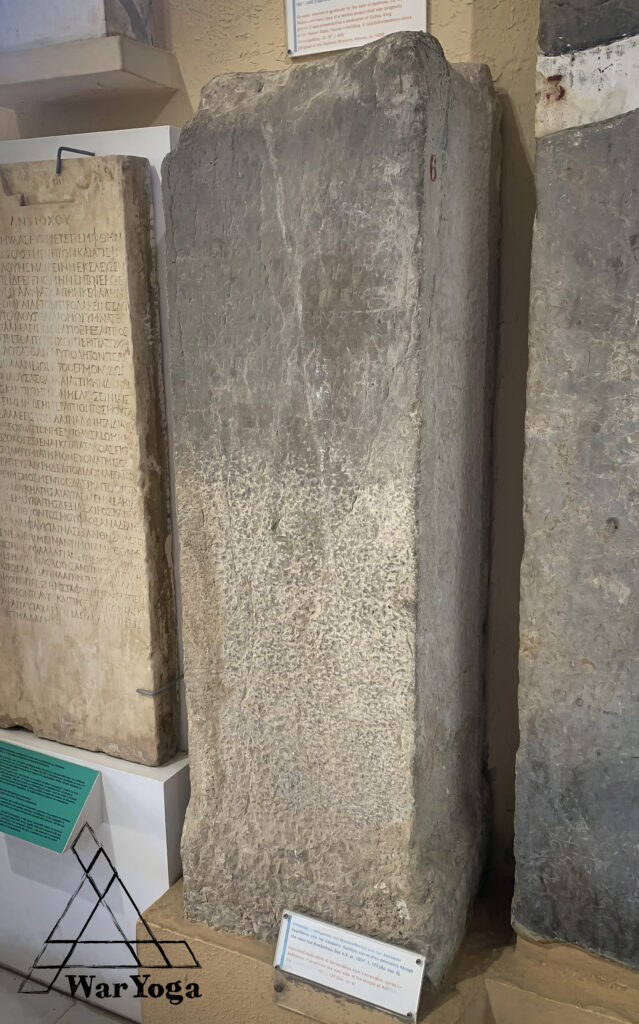

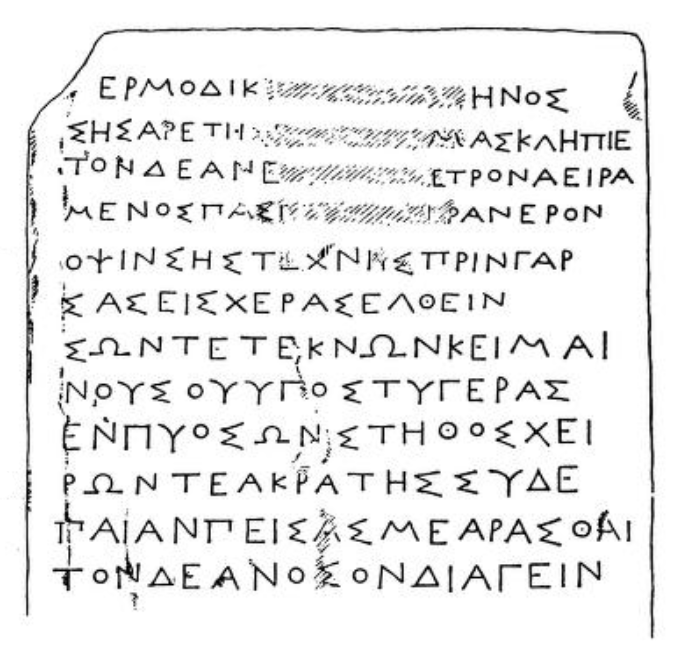

Hermodikos Stone

The ancient sanctuary of Epidauros was the sacred site of the healer god Asklepios. People from across the ancient world would come to the sanctuary to obtain relief from their maladies and afflictions. It was both a sacred site and a hospital with doctors giving treatments on behalf of the god.

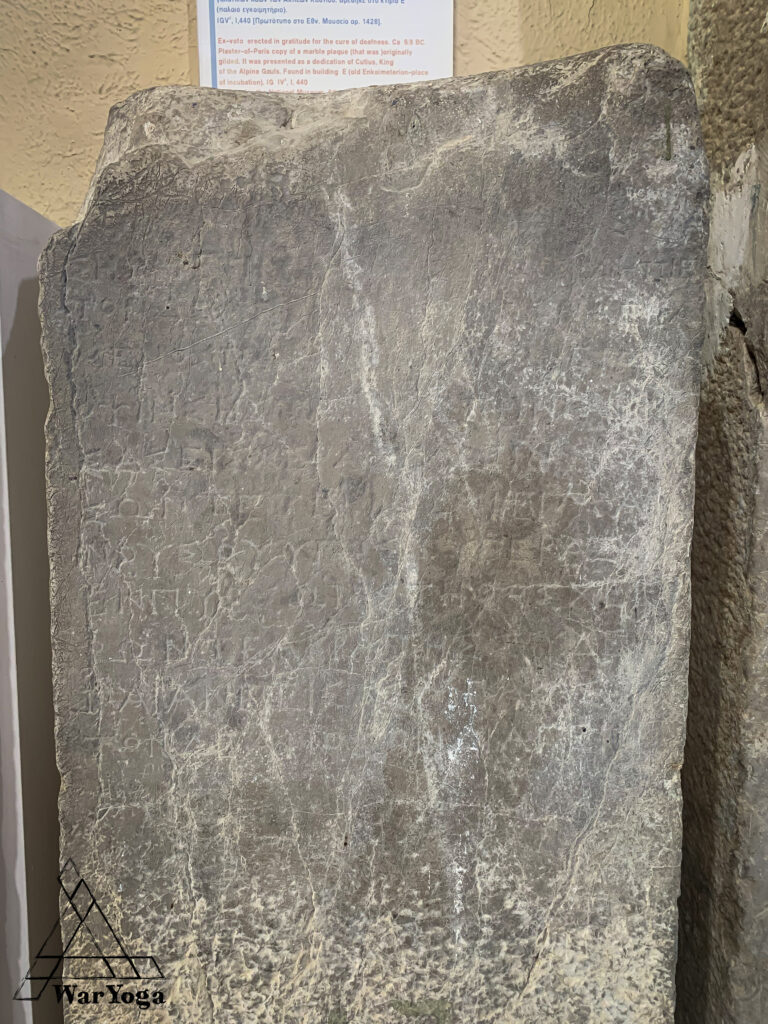

At the Archaeological Museum of Epidauros, two stones from the 3rd century BCE sit either side of the main entrance, along with several others. These two, however, are of particular interest to anyone interested in Stonelifting. The first lists people cured by the god Asklepios. On the list is the following entry:

“Hermodikos of Lampsakos; bodily weakness. The god cured this man as he slept, and ordered him when he came away to carry into the temple the largest stone he could. He carried the stone which now stands in front of the shrine.”

Fortunately, this stone survives too, although the museum list it simple as “a dedication by Hermodikos.” The stone actually reads:

“Hermodikos of Lampsakos. As proof of Thy merit, Asklepios, I dedicated this stone which I lifted myself, plain for all to see, clear evidence of Thy skill; for, before I came into Thy hands and the hands of Thy servants, I lay sick of a foul disease, congestion of the lungs and utter bodily weakness; but Thou, Healer, persuadedst me to pick up this stone and to live completely cured.”

The rectangular block has a dip in the top and is shaped as though it were used as an altar of sorts. It was found in the precinct of the Temple of Asklepios in front of the altar of the god. It weighs 334 kg (674 lb) and could only really be carried as a hug lift, much like some of the Icelandic stones, but it would still be a phenomenal feat of strength.

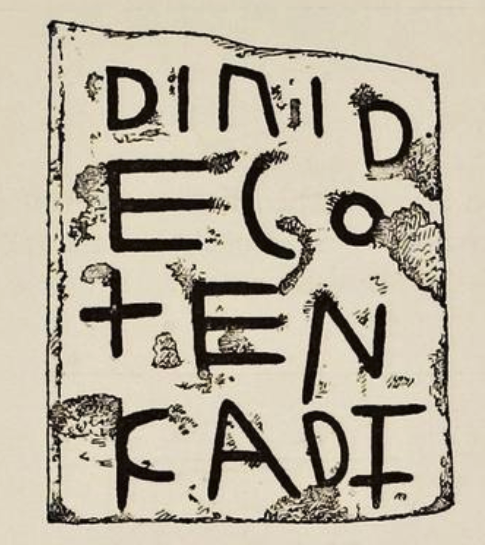

Throwing Stone of Xenareos

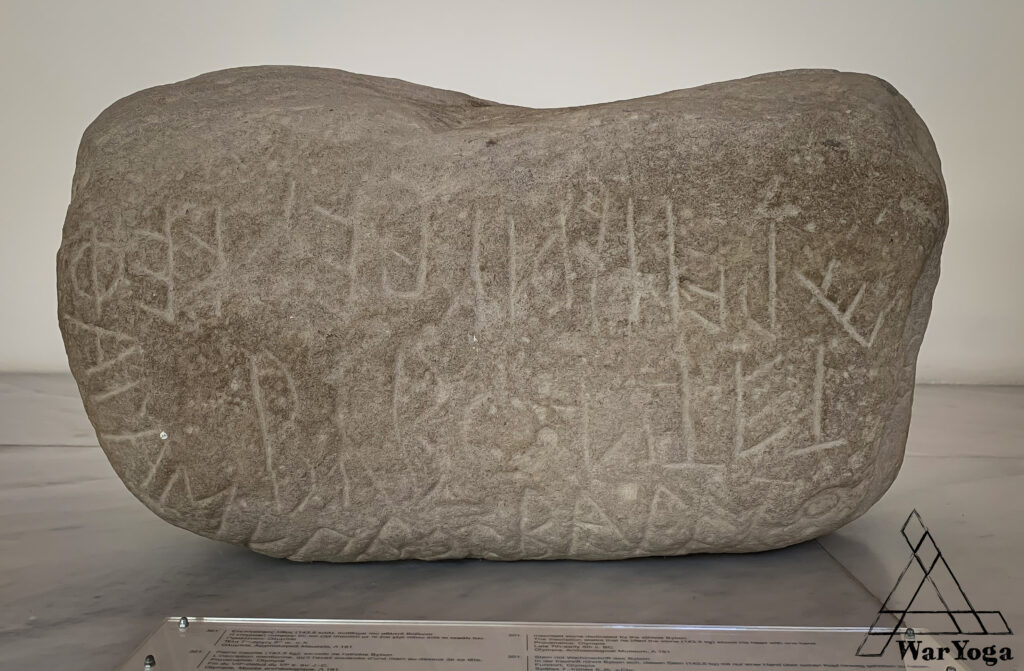

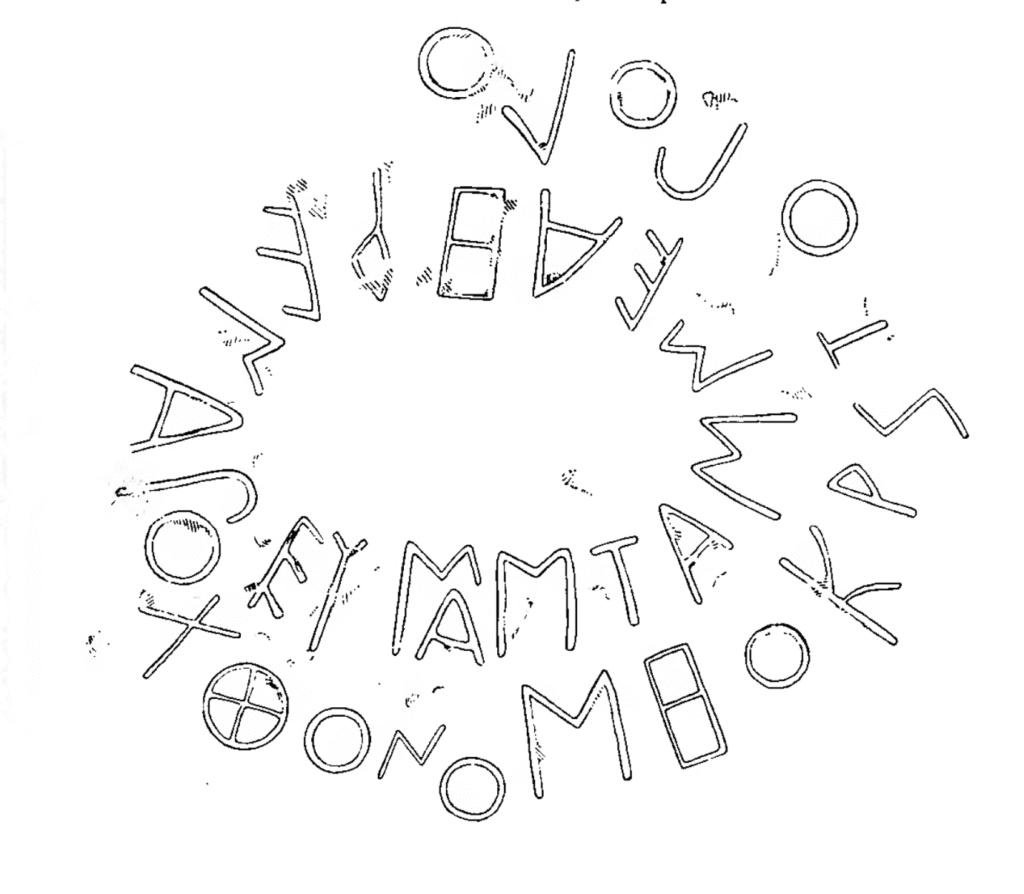

The last stone was the most elusive one to find. Harris had a very brief description of it and stated that it was found in a wall in the Kladeos Valley about two kilometres from Olympia. He stated it weighs around 100 lbs. After a little help from some friends in Olympia, in particular George Tsavaras, I managed to get hold of the inscription details and a drawing of the stone in the 1896 record of inscriptions by Curtius and Adler published in Berlin following the German excavations of that time.

The record stated that it was found in a wall in Koskina on the 13th of June 1880 and that at some point in its history it had been cut to fit in the wall. The stone, had perhaps been plundered from the Olympic sanctuary and one sat near to the Bybon Stone as a dedicated offering to Zeus or Pelops. After searching all over the museums at Olympia, I could not find the stone. Nobody had ever heard of the stone.

I managed to make my way to the office of Konstantinos Antonopoulos an archaeologist at the Ephorate of Antiquities of Elia who was extremely helpful and suggested that I apply to see the stone, if it was there, in the museum storeroom. A week or so later, I was granted permission and my new friend Konstantinos was there to greet me after my long drive back to Olympia from Athens.

Entering the storeroom, I was taken to the back and there on a shelf was the Throwing Stone of Xenareos. It was put on a table right in front of me. It weighs around 100 lbs, is made of poros limestone and has some visible shells in it. It has been dressed significantly and its original size and shape are impossible to discern. On it is the inscription:

“I am the Throwing Stone of Xenareos.”

Of profound antiquity, it likely at least the same age as the Bybon Stone, as it uses a character called a digamma that fell out of use in Greek before the Classical Period. It is an incredible artifact that unfortunately will remain in the storeroom until enough support can be mustered among the archaeological community of Greece to convince the Ephorate that it should be in display next to the Bybon Stone at the museum.

The lifting stones of ancient Greece are cultural treasures. They remind us not only that strength has been valued since time immemorial, but that when we lift stones we are part of an unbroken line that stretches back in time to our deepest ancestors. We must preserve them and also present them so that future generations can continue to be inspired by the feats of the men whose names are preserved upon them.