Was there an Ancient Greek boxing dance before Pygmakhía fights in antiquity?

Across many cultures, a dance precedes combat. This ritual aspect to fighting is intrinsically linked to the sacrificial nature of boxing. Aside from the well-known Ram Muay of Thailand and the Lethwei Yay of Myanmar, the Iranians engage in a ritual dance before Koshti Gile Mardi wrestling, and the Indians perform a dance of sorts before Kushti wrestling.

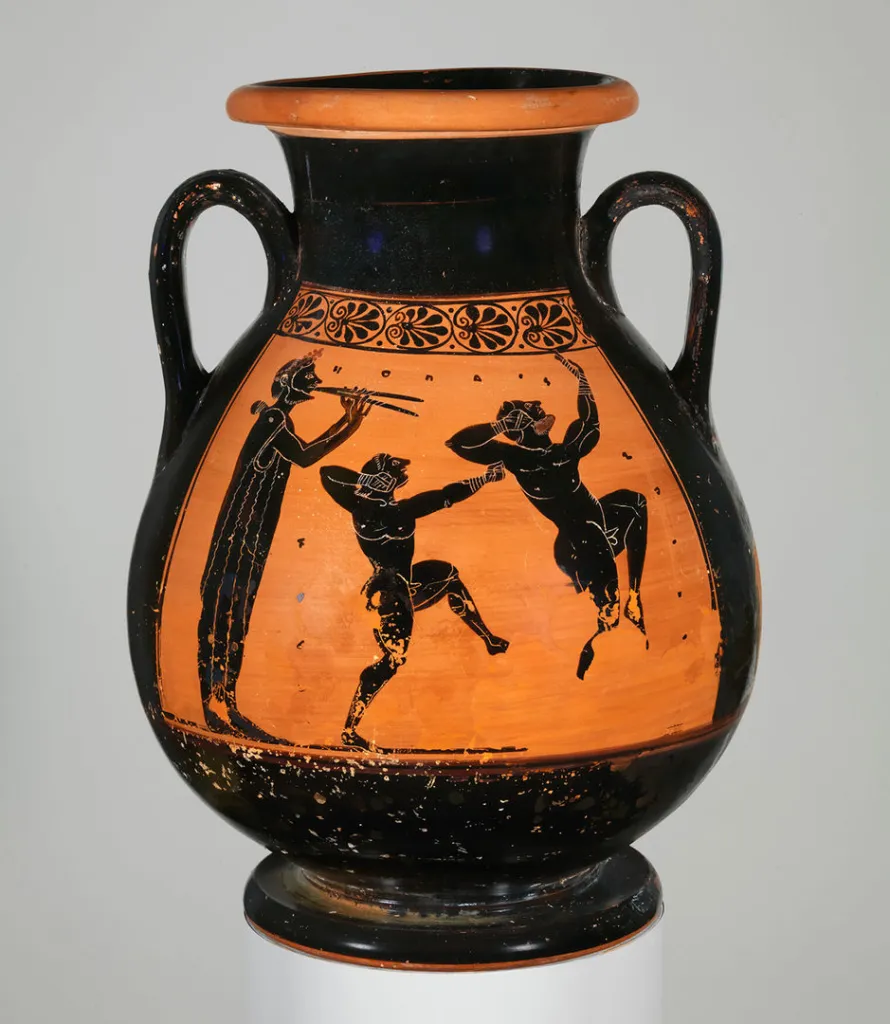

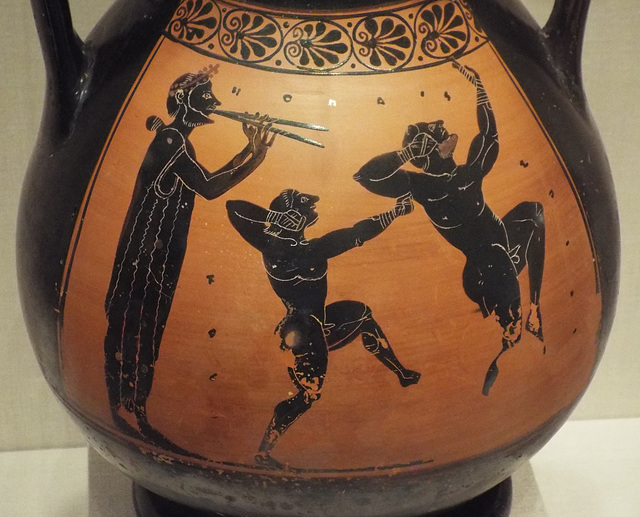

Did the Ancient Greeks have the same? The evidence for this possibility comes in the form of a black figure pelike vase from 510 BCE by the Acheloös Painter in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as some literary clues. The most compelling evidence, however, comes from across the Adriatic Sea in what is now Italy, but was once Etruria.

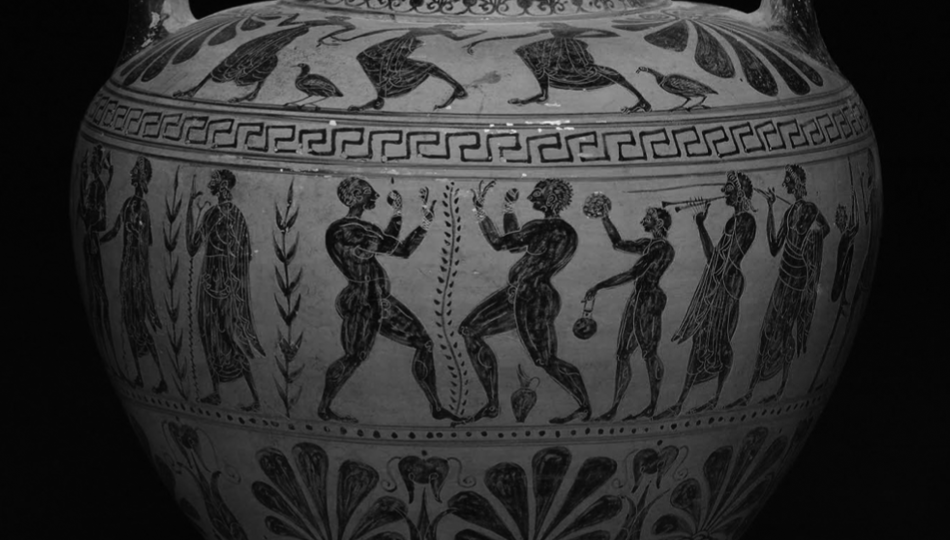

Late Etruscan tombs, dating from 520 – 470 BCE, such as the Tomba Cardarelli, Tomba delle Iscrizioni, and Tomba della Scimmia, feature boxing scenes, with almost identical depictions as seen in Greek art of the period. There is a key difference in many of these scenes, however: the boxers are in poses that are indistinguishablle from dancer depictions in the same tombs (aside from the distinctive hand wraps), and they are always bloodless.

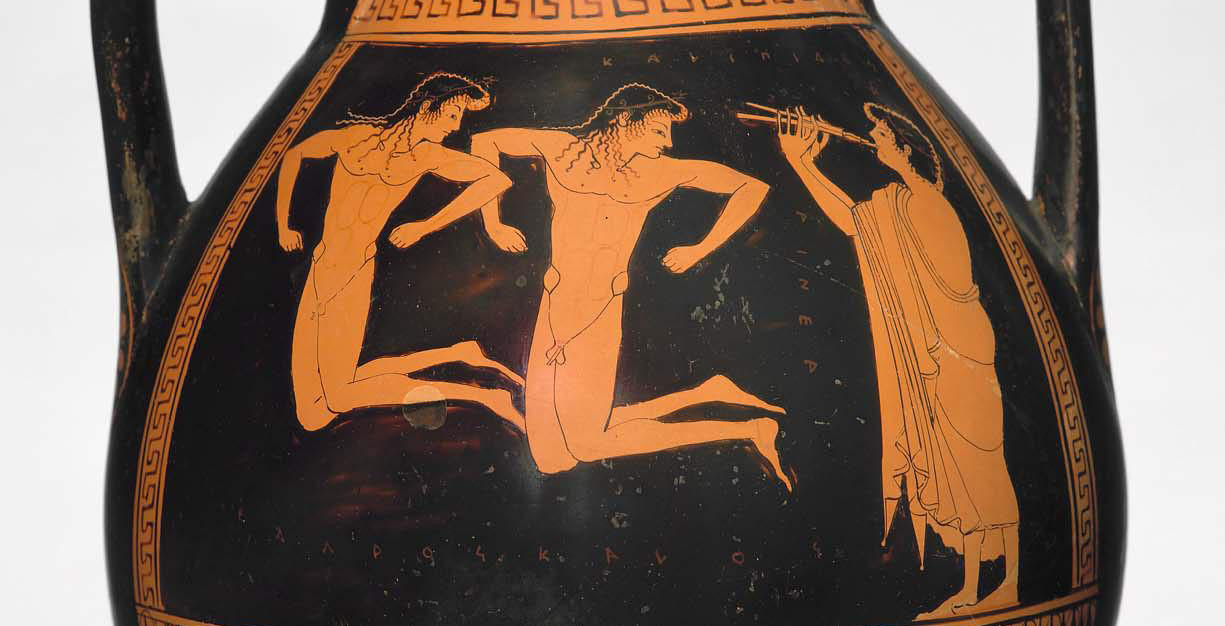

Tombs like Tomba Cardarelli and Tomba della Fustigazione feature boxers in these “dancing” positions either side of an entrance doorway, acting as apotropaic guardians of sorts. Another feature is that the dancing boxers are almost always accompanied by a pipe player. The tibia (Greek aulos) is often associated with processions and games, but the Greeks only played the aulos for the long jump of the pentathlon by the 6th century BCE.

However, the Greeks noted that the Etruscans played pipes while boxing. Athênaios of Naukratis explicitly mentions this in the 3rd century CE:

“And Eratosthenes says, in the first book of his Catalogue of the Victors at Olympia, that the Etruscans used to box to the music of the flute.” Athênaios of Naukratis, Deipnosophistaí 4.154a

and

“But the Etruscans (as Alkimos relates) are so far gone in luxury, that they even make bread, and box, and flog people to the sound of the flute.” Athênaios of Naukratis, Deipnosophistaí 12.518b

The Etruscan boxers also performed at Roman Ludi (“Games”) according to Livy:

“The entertainment was furnished by horses and boxers, imported for the most part from Etruria. From that time the Games continued to be a regular annual show, and were called indifferently the Roman and the Great Games.” Livy, History of Rome 1.35

These Ludi included processions in which included dancers and performers with tibia:

“Players who had been brought in from Etruria danced to the strains of the flautist and performed not ungraceful evolutions in the Tuscan fashion” Livy, History of Rome 7.2

Kyle A. Jazwa in his article A Late Archaic Boxing-Dance in Etruria: Identification, Comparison, and Function (De Gruyter, Etruscan Studies 2020; 23(1–2): 29–61), argues that this evidence all points to the existence of an Etruscan boxing-dance.

The Etruscans certainly entered into a cultural exchange with the Greeks and became an important export market for ceramics that the Greeks produced specifically for the Etruscan market. They also, over time, took on many of the trappings of the Greek elite, mimicking the Aristoi in many respects.

This was likely not a one-way cultural exchange, and the Greeks may have taken some things from the Etruscans, a fellow Indo-European people. Did they adopt an Etruscan boxing dance at some point in time, or did they have their own?

The pelike vase is the only clear depiction of what looks like an Ancient Greek boxing dance. In the normal artistic convention for vase painting, both black and red figure, has the two boxers squaring off or fighting, always facing each other, sometimes with blood pouring from one or both fighters. In the 6th century pelike, the boxers are both facing the same direction and there is an aulos player in the position normally reserved for a judge or trainer. The vase is of Attic origin and was not made for the Etruscan, but for the domestic Greek market. This seems like an outlier.

There is, however, another critical piece of evidence from the 2nd Century CE Greek traveller Pausanías. Pausanías describes a chryselephantine chest in the temple of Hera at Olympia which, among other things, depicts the funeral games of Pelias:

“Those daring to box are Admetos and Mopsos son of Ampyx; a man stands between them playing the flute, just as in our time the practice is to play it in the jumping for the pentathlon.” Pausanías, Description of Greece 5.17.10

This scene stood out to Pausanías, as the aulos was, by the 2nd century CE, absent from Pygmakhía bouts.

The question remains, was the aulos played in deeper antiquity during the boxing matches of the Greeks, and if so, did the boxers dance before fighting much like their Indo-European cousins and beyond did and do still to this day?

Since the Ancient Greeks had an armed war dance called the Pyrrikhios, which also continues to this day among the Pontic Greeks, it would be almost stranger if there wasn’t an Ancient Greek boxing dance.